Crepapelle ENG

Riccardo Giacconi

Crepapelle

2015

It was meant to be funny, I said, knowing they couldn’t possibly believe me.

– Milan Kundera, The Joke, 1967

“Don’t you think contemporary art takes itself too seriously?”

I was asked this question by a friend of mine, a physicist, as we were leaving an art exhibition. I immediately tried to answer back, mentioning works by Maurizio Cattelan, Richard Prince, John Baldessari, Fischli & Weiss, including Piero Manzoni and Francis Picabia. “I find them very funny”, I told him. “Yes, maybe”, he replied, unconvinced “but I mean something that makes you laugh your head off, a crepapelle, like when you watch The Simpsons' best episodes, or you read Three Men in a Boat”.

After reflecting about it, I had to admit that he was right in some way. Not only couldn’t I think of a piece of contemporary art that made me laugh my head off; I couldn’t even recall anyone telling me they’d had this kind of experience.[1]

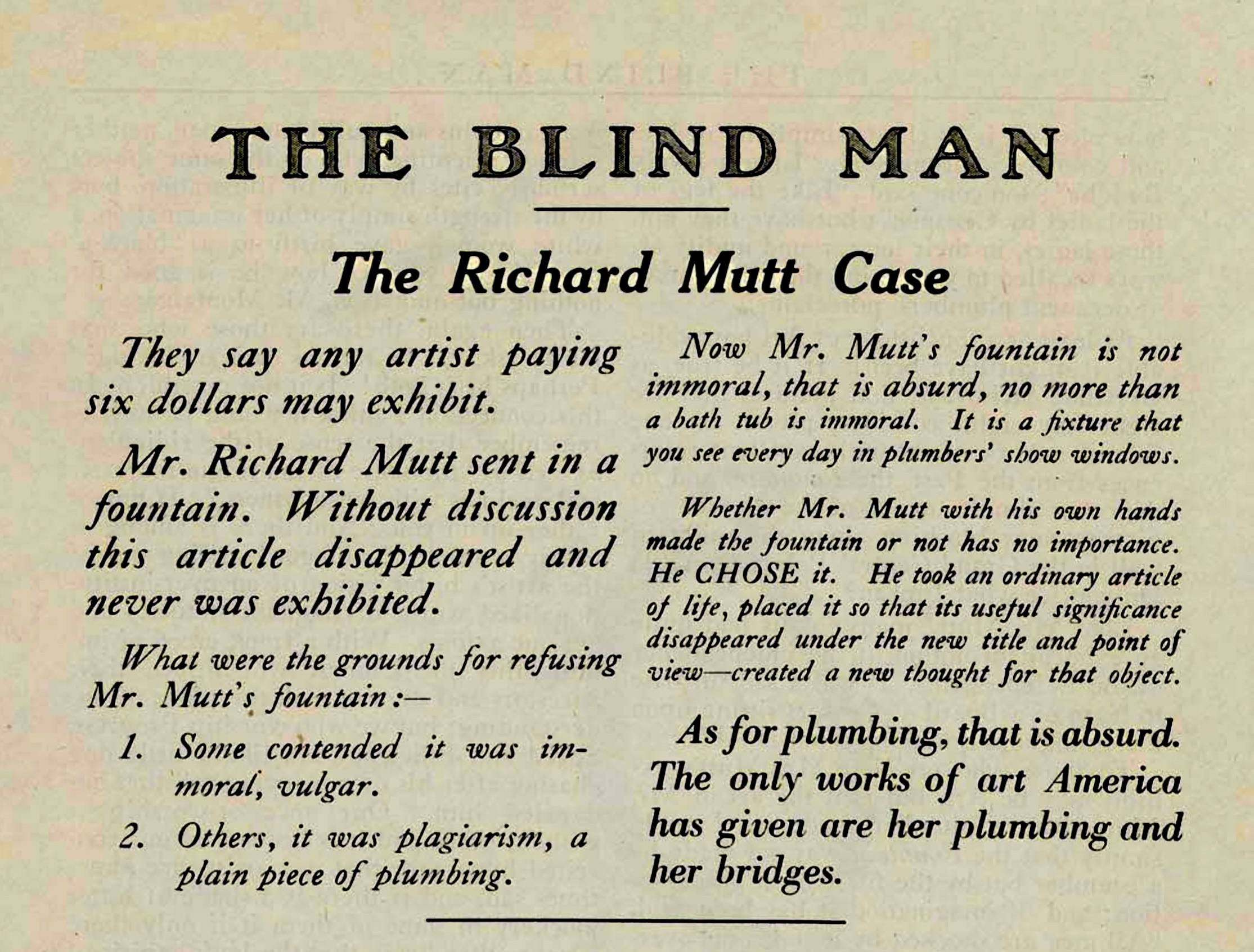

But I didn’t give up, and I told him about the text that Marcel Duchamp published (with Henri-Pierre Roché and Beatrice Wood) in the magazine “The Blind Man” in 1917. It dealt with the exclusion of Fountain, his notorious upturned urinal, from the exhibition organized by the Society of Independent Artists in New York. The text defended the fictional artist Richard Mutt, alleged author of the work:

What were the grounds for refusing Mr Mutt's fountain:–

1. Some contended it was immoral, vulgar.

2. Others, it was plagiarism, a plain piece of plumbing.

Now Mr Mutt’s fountain is not immoral, that is absurd, no more than a bathtub is immoral. It is a fixture that you see every day in plumbers’ shows windows. [...]

As for plumbing, that is absurd. The only works of art America has given are her plumbing and her bridges.

I told my friend about this text as if it were a joke. That is what it always seemed like to me, with its perfect punch line – a sharp remark on the American artistic context of the time. I explained that the text was also one of the first theoretical formulations of the ‘ready-made’. Therefore, our idea of contemporary art is, in some way, founded on it – especially on this fragment:

Whether Mr. Mutt with his own hands made the fountain or not has no importance. He CHOSE it. He took an ordinary article of life, placed it so that its useful significance disappeared under the new title and point of view–created a new thought for that object.

“The Blind Man” n.2, 1917 (part.)

“That’s why!” my friend replied after some thought; “If it’s true that contemporary art began with a joke, I’m not surprised that it must constantly take itself so seriously”. So we began reflecting on how art history would have been different if Duchamp’s “joke” had not been taken seriously. What if the Western idea of contemporary art had not been built on that joke?

My physicist friend then started to tell me about the ‘Sokal affair’. In 1996 the influential academic journal of cultural studies Social Text published the essay Transgressing the Boundaries: Towards a Transformative Hermeneutics of Quantum Gravity by American physicist Alan Sokal. The article, full of quotes from eminent postmodern thinkers, aimed not only to reveal the capitalistic, patriarchal and militaristic nature of traditional mathematics, but also to demonstrate how “postmodern science provides a powerful refutation of the authoritarianism and elitism inherent in traditional science”.

The same day the essay was published, Sokal revealed in another journal that it was a joke, describing it as “a pastiche of left-wing cant, fawning references, grandiose quotations, and outright nonsense, […] structured around the silliest quotations I could find about mathematics and physics”. Transgressing the Boundaries, therefore, was not to be taken seriously. Its real aim was to show how a text, even if total nonsense, could be accepted by a cultural system if plausibly presented and provided with the vocabulary in vogue among ‘experts’.[2]

Anton Raphael Mengs, Giove che bacia Ganimede, 1759

I replied by telling him about a joke played by painter Anton Raphael Mengs to his friend, renowned art historian Johann Joachim Winckelmann. In 1759 Mengs made a fresco (Jupiter kissing Ganymede) in the manner of an ancient Roman painting, imitating the scrapings, the restorations and the craquelure. Winckelmann fell into the trap: not recognizing the fake, he defined it as “one of the most beautiful figures to survive from antiquity”.

I remember an anecdote Giorgio Agamben used to tell us during his seminars in Venice. It concerned the medieval theologian Pierre de Poitiers, who contributed, with a singular theory, to the dispute on the validity and effectuality of the sacramental liturgy.[3] At the time, the problem was how to decide whether a sacrament was valid, no matter who administered it. For instance would a baptism be valid even if the priest who celebrated it was a thief, an apostate or a murderer?

After a lengthy debate, the Church decided that no matter the moral character of the priest, the baptism would be valid anyway. However, Pierre de Poitiers’ theory specifies that the only cause sufficient to nullify a baptism is if the priest who administrates it is joking. In other words, only a joke has the power to nullify a sacrament.

This thesis clearly reveals the destructive potential of the joke, a device capable of disabling the dichotomy between truth and fiction. The joke has nothing to do with being true or false; it rather concerns a performative realm in which a community, even the smallest one, decides to accept the existence of a certain reality. Simon Critchley speaks of “a tacit agreement about the social world in which we find ourselves as the implicit background to the joke; [...] a sort of consensus or implicit shared understanding as to what constitutes joking for us”[4].

Similarly to how a joke could undermine the foundations of liturgical sacraments, today’s art regime would be radically questioned if we were not to take seriously its foundations (such as Duchamp’s formulation of the ready-made). Structural similarities have often been identified between religion's systems of values and beliefs, and the social institution of contemporary art.

The philosopher of religions Mark C. Taylor asserts that: “In finance capitalism, wealth is created through the circulation of signs. […] As art becomes a progressively abstract play of non-referential signs, abstract financial instruments increasingly create an autonomous sphere of circulation whose end is nothing other than the endless proliferation of monetary and financial signs. When the art of finance becomes the finance of art, art is no longer merely a commodity to be bought and sold, but […] it is traded like any other financial asset”[5]. As an object of enormous economic investments, contemporary art has the structural need to be taken extremely seriously.

Angus Fairhurst, Gallery Connections, 1991. Courtesy The Estate of Angus Fairhurst

The sound installation Gallery Connections (1991) by Angus Fairhurst makes fun of the very same seriousness of art economics. Among the Young British Artists, Fairhurst was probably the one who employed most brilliantly the typical British wit. Not simply an installation or a sound work, Gallery Connections's medium seems to be the joke itself. The artist recorded a series of contrived telephone exchanges between unwitting gallery employees: Fairhurst rang two different contemporary art galleries simultaneously and then held the handsets together, remaining silent. The speakers, initially disoriented, gradually became more hostile, as in typical prank calls. Fairhurst’s work generated chaos among the London galleries, which for a few days avoided using the telephone, fearing the Inland Revenue was bugging them. The transcriptions of the Gallery Connections were later published in the first issue of frieze magazine.

Some time after the conversation with my physicist friend, I had lunch with Israeli artist Roee Rosen. I told him about my questions regarding jokes and art. He totally disagreed that contemporary art is not capable of making people laugh. He told me about an essay[6] he wrote on the juxtaposition between, on the one hand, irony, sadism and Bruce Nauman, and on the other hand, humour, masochism and Vito Acconci. The distinction between irony and humour is traditionally linked to the spatial duality between inside and outside: the first uses language distancing itself from it and, according to Freud, “imparting the very opposite of what one intended to express”. Humour, instead, always operates from within: it is “a means of obtaining pleasure in spite of the distressing effects that interfere with it” in the situation in which one finds oneself: “it puts itself in their place”[7].

According to Rosen, irony and sadism belong to the same conceptual axis, which traverses several of Bruce Nauman’s works. An example is the 1987 video-loop Clown Torture (Dark and Stormy Night with Laughter), in which the torture of a clown consists in the incessant repetition of an endless nursery rhyme: “It was a dark and stormy night. Three men were sitting around a campfire. One of the men said, ‘Tell us a story Jack.’ And Jack said, ‘It was a dark and stormy night. Three men were sitting around a campfire. One of the men said...’”.

Some works by Vito Acconci, on the contrary, are traversed by the humour/masochism axis. For example: Seedbed (1972), the well-known performance in which the artist, hidden underneath a ramp, was masturbating while telling fantasies about the visitors walking above him, his voice transmitted through loudspeakers in the gallery.

Roee Rosen, Hilarious, video still, 2010. Courtesy the artist

Roee Rosen’s interest in the mechanisms of laughter is at the basis of his video Hilarious (2010), starring Israeli-American actress Hani Furstenberg in front of a television studio audience. In the form of a stand-up monologue, she tells a series of news items about death, violence and politics, often linked to the Israeli context and mixed with stories and jokes resembling the Jewish ‘Witz’ analyzed by Freud. According to Rosen, “Hilarious is set to examine the possibility of dysfunctional humor and laughter stirred when there is no reason to laugh. […] If humor is a mechanism set to cope in particular ways with disturbing, sometimes forbidden topics, this performance not only offsets these structures through their failure, but also offers a different manifestation of these topics, left exposed without the guise of laughter”.[8]

Following Roee Rosen’s indication, I read the most famous studies on the mechanics of laughter: Freud's and Bergson's. I was surprised to encounter several references to the analogy between art and joke. In his essay on Jokes and their relation to the unconscious, Freud noted that jokes structurally need an audience, because “no one can be content with having made a joke for himself alone. [...] Something remains over which seeks, by communicating the idea, to bring the unknown process of constructing the joke to a conclusion”[9]. Bergson, in Le Rire, pointed to the fact that “our laughter is always the laughter of a group”, given that “laughter must answer to certain requirements of life in common”[10].

Such observations could easily be applied to what we consider art today. Freud also noted that the existence of the joke is conditioned by the willingness to accept it as such: “only what I allow to be a joke is a joke”. Dino Formaggio’s tautological definition, dated 1981, comes immediately to mind: “art is everything that mankind calls art”[11]. Bergson was even more explicit when he stated that “the comic comes into being just when society and the individual [...] begin to regard themselves as work of art”: the comic “oscillates between life and art”.[12]

When I met my physicist friend again, I told him a story that I then discovered to be a variation of one of Freud’s ‘Witze’:

Duchamp borrowed a bicycle from Picabia. Upon returning it, he was sued by his friend, because the bicycle was missing the front wheel and was therefore unusable. In his defence, he said: “In the first place I have never borrowed any bicycle from Picabia; secondly, the bicycle was already lacking a wheel when I received it from him; thirdly, the bicycle was in perfect condition when I returned it.”

[1] Cfr. What’s so funny?, symposium on art and humour organised

on 14 October 2014 during Frieze Art Fair (participants: Nathaniel Mellors,

Aleksandra Mir, Roee Rosen and Olav Westphalen).

[2] Alan D. Sokal, “A Physicist Experiments With Cultural Studies”, Lingua Franca, May/June, 1996.

[3] Cfr. Giorgio Agamben, Liturgia and the Modern State, European Graduate School Video Lectures, http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=jK-s3qHfLgw Transcription: http://automatist.net/deptofreading/wiki/pmwiki.php/Liturgia

[4] Simon Critchley, Did You Hear The One About The Philosopher Writing A Book On Humour?, Richmond Journal of Philosophy 2, 2002.

[5] Mark C. Taylor, Financialization of Art (January 28, 2013), in “Capitalism and Society”, Vol. 6, Issue 2, Article 3, 2011.

[6] Roee Rosen, Sore Eros Conversions. Aggression and Submission in the Art of Bruce Nauman and Vito Acconci, Studio Art Magazine n. 55, 1995.

[7] Sigmund Freud, Der Witz und seine Beziehung zum Unbewußten, 1905 ((English translation by J. Strachey: Jokes and their relation to the unconscious, W. W. Norton, New York 1960).

[8] “Hilarious is set to examine the possibility of dysfunctional humor and laughter stirred when there is no reason to laugh. If humor is a mechanism set to cope in particular ways with disturbing, sometimes forbidden topics, this performance not only offsets these structures through their failure, but also offers a different manifestation of these topics, left exposed without the guise of laughter.” Cfr. Roee Rosen, Towards the work Hilarious – Former Cases of Dysfunctional Humor, http://roeerosen.com/tagged/Writings-by-RR

[9] Sigmund Freud, op. cit.

[10] Henri Bergson, Le rire, Paris, 1900.

[11] Dino Formaggio, L'arte come idea e come esperienza, Mondadori, Milano 1981.

[12] Cfr. anche Situation Comedy: Humor In Recent Art (Independent Curators International, 2005); When Humour Becomes Painful (JRP|Ringier, 2005), The Artist's Joke (MIT Press – Whitechapel, 2007); Black Sphinx: On the Comedic in Modern Art (JRP|Ringier, 2010).