– Alberto Camerini

Riccardo Giacconi

Harlequin, Punk, Robot

May 2017

An essay on a series of conversations with singer/songwriter Alberto Camerini.

Published on the magazine Linus and on the website Le Parole e le cose.

English Version

Italian Version on Le Parole e Le Cose

Italian Version on Linus (PDF)

The spectacle has spread itself to the point where it now permeates all reality. […] Men resemble their times more than their fathers. […] When the spectacle stops talking about something for three days, it is as if it did not exist. […] A present has been manufactured where fashion itself, from clothes to singers, has come to a halt. Fashion wants to forget the past and no longer seems to believe in a future.[1]

The first time I meet Italian singer/songwriter Alberto Camerini, I show him these fragments from Guy Debord’s Commentaries. I tell him, rather naively, that I see him as an emblem of the transition from the Seventies to the Eighties in Italy – a transition that is still sometimes referred to as riflusso (“reflux”). «No, I am not the symbol of anything», he stops me immediately, after taking a copy of The Society of the Spectacle from his shelf. «However... Ebb and flow. Flusso, riflusso. Fluxus: I think it was an artistic movement. In 1975 the United States lost the Vietnam War. After winning for ten years in a row, the Italian Communist Party had its ebb in the 80s. But it was not my fault: ebb and flow occurred anyway. Like a reporter, I wrote a piece on the flow in the 70s and a piece on the ebb in the 80s».

I tell him I would like to make a documentary film about him. He accepts, albeit reluctantly. We meet again at his house after a few days, to record a first interview. As soon as we sit down, he warns me: «I’m making a big effort, because I don’t like to bring up my past. I’m not narcissistic enough, unlike those who cry when they listen to their own songs. Confessions make me feel a bit uncomfortable – I don’t believe in psychoanalysis».

I ask him if he regrets never having been considered an intellectual. «It’s best that you know», he interrupts me. «My life has two dimensions: a public one and a private one. If you want to make a documentary about the private one, it’s fine, because when I die, they’ll say, “He was not as stupid as he looked.” Instead, the public dimension is ephemeral, and I try to be careful not to have it destroyed. I’m aware that my work is all in those three minutes, and that’s already a lot. The two songs I’m known for, they are worth a lifetime. At least, that’s what they told me. All the rest doesn’t exist; it doesn’t fit in the three minutes of Rock 'n' roll robot and Tanz bambolina. No one is given more time.»

In the following days I study Alberto Camerini’s career and I listen to all his records. I learn of his passion for the Venetian Settecento (18th Century). At our following meeting I bring him a book I have just finished: Pulcinella ovvero Divertimento per li regazzi[2]. It is the book devoted by Giorgio Agamben to the figure of Pulcinella, illustrated with numerous etchings and paintings by Giambattista and Giandomenico Tiepolo. I ask Alberto Camerini to read a paragraph I have underlined, which reminds me of how he described his life divided into two:

Have I really lived my life, or is there something left in it, which I have been unable to live? This non-lived part of my life is like a faceless stowaway, who follows me day after day, and whom I can never catch to speak to.

Since our last meeting, I have begun to reflect on a possible leitmotif for the documentary: a parallel between Camerini and Tiepolo, between the social and political contexts in which they have spent their careers. After reading the fragment by Agamben, Alberto Camerini takes me to his kitchen. Hanging on the wall, he shows me two large framed posters. On the left is a poster advertising Goldoni’s play Arlecchino servitore di due padroni (“Harlequin Servant of Two Masters”) directed by Strehler at the Teatro Piccolo in Milan. The poster on the right, to my great surprise, is dedicated to Giambattista Tiepolo: it reproduces a painting housed in the Scuola Grande dei Carmini, in Venice. One next to the other, above the dining table, Harlequin and Tiepolo, like two tutelary deities.

Perhaps my idea of a parallelism is not that odd, after all. «Tiepolo and the Venetian Settecento have been my first and deepest inspiration», he confirms. «Venice at that time was composed of opera backdrops. It’s the last farewell of the Venetian Republic before the French Revolution. Tiepolo is enjoyable, he’s a painter attuned to my aesthetics: the aesthetic of hedonism, rather than the aesthetics of revolutionary social protest. There’s an aesthetics of pain and protest, and then there’s a hedonistic, cosmetic aesthetics, which tends to erase the ugliness of society.»

Alberto Camerini sees Giambattista Tiepolo as a sort of archetype of his departure from the radical Left. We start talking about the firstborn of the painter, Giandomenico, whose life provides an even more fitting example: in the last years of the millennial Republic of Venice, he flees to the mainland, to the family villa in Zianigo. There, he starts working on a series of frescoes dedicated to Pulcinella, which he completes precisely in 1797, the fateful year marking the fall of the Serenissima. Giorgio Agamben, in an interview, explains his interest in this series of frescoes, now hosted in Venice at Ca’ Rezzonico:

For Giandomenico Tiepolo, Pulcinella is what survives the end of his world, the death of Venice as he had known and loved it and – in this sense – the end of politics. But in spite of everything, he is not simply a non-politic figure. [...] His gags and gestures show what a body can do when it can no longer act politically. That is why he interests me. I think that the model of politics as we know it, based on action and struggle, has become obsolete in the context where we live, dominated by the economy and the Security State.[3]

«I define it as folk, urban, proletarian, contemporary», declares Alberto Camerini about his music in a 1980 TV interview, at the beginning of his most successful period. «Harlequin has always been very rock ‘n’ roll, he’s always been singing folk music, he’s always jumped and danced», he states in another interview. I ask him what he saw, at the time, in Harlequin. His answer outlines the whole constellation of his references. «Proletariat, poverty, hunger. Robot, Harlequin, punk: hunger. Hunger. They all come from a low social class. Harlequin is the hero of the lost and the forgotten, as Alberto Camerini. How should I put it – I connect my Harlequin with the international electronic scene. A little character, an electronic puppet, video games... But now I’m old, as you see – everything is different. I remember when I could still play that character. Now... talking about sex: my audience was mainly composed of virgin women – girls who wanted puppets, dolls, masks.»

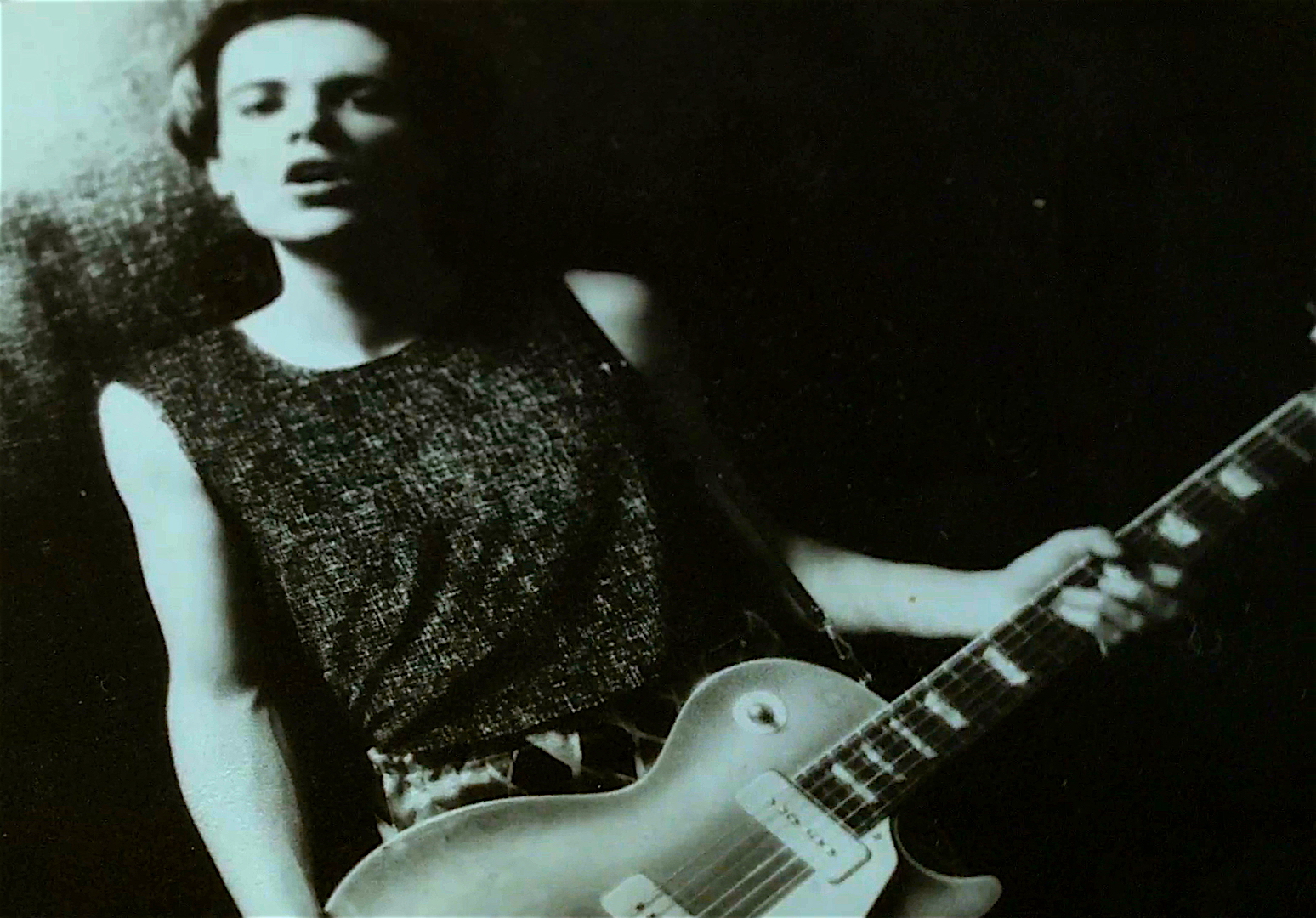

Camerini’s trademark style in the early Eighties is a mix of pop, punk, electronic music and Commedia dell’Arte. Subjects such as technology and computers recur in many of his songs (Sintonizzati con me, 1980; Bip Bip Rock, 1981; Maccheroni Elettronici, 1982; Computer Capriccio, 1983). The robot appears also as a recurring topic (Neurox, 1978; Il re di plastica, 1980; Rock ‘n’ Roll Robot, 1981; Tanz Bambolina, 1982), very often in parallel with Harlequin. His own stage costume, his persona, is a mix between a Harlequin, a punk and a robot.

Since our first meeting, Camerini makes it clear that he does not want to talk about politics. Yet, we end up talking about it every time, for instance when I ask him about his beginnings, about Milan in the Seventies. «I was living in a dream, in a Harlequin world, a microcosm of stories revolving around a central character. It was a separate, independent world – the world of May 1968. I was schizophrenic even then: multiple personality. I changed my clothes quickly – I would smoke weed with American-like hippies, and then hang out with revolutionary left-wing workers’ organizations, where joints were out of the question. I miraculously combined the pro-Soviet Stalinist working class’ atavistic hatred with the libertarian light-heartedness of long-haired American intellectuals. In that period I read about Mao Zedong’s Long March. I criticized the only thing I could criticize: the Left, the Communist Party. My father was a communist, and I was even more to the left. Student activism, Lotta Continua, Avanguardia Operaia... We would read Marx’s Capital, but not the whole thing – just excerpts on the cyclostyled leaflets we were given to study. And then we would end up in Lambro Park to smoke weed and hope to see naked girls – which rarely happened.»

The great success comes at the beginning of the Eighties, when he leaves the legendary indie label Cramps Records and joins CBS, a major. Rock 'n' Roll Robot is released in 1981, Tanz Bambolina a year later. They will remain his only real hits. I ask him how he managed to break through. «It was thanks to Eugenio Finardi [fraternal friend and fellow songwriter], and to my ego conflicts with him. Because I wanted to be Mick Jagger, not Keith Richards. Those were kids’ quarrels, but we both knew that we wanted to be famous, we wanted to be rock 'n' roll superstars. Thanks to him, I departed the revolutionary Left, which wouldn’t allow me to become David Bowie, that is, to become a pop star, a professional, regular superstar. Then, I turned professional and gradually I transformed from a lapdog into an idol. People started to stop me in the streets. At restaurants and on the beach they asked for my autograph. Actually, they would have stared at me anyway, because of my hairdo. But they stared and they knew who I was, because I was on the cover of all the girls’ magazines.»

Before I leave, I ask Alberto if he has any archive footage for me to use in the documentary. He gives me some VHS-C cassettes. Mainly, they are amateur recordings of his concerts between the Nineties and the first 2000s, when his great success was already over. Camerini is recorded while he performs in the summer, mainly in Southern Italy. Between a concert and another, he films many close-ups: a storefront full of masks in Milan; statues of saints carried in procession in Puglia; a puppet theatre in a gas station; details from art history books.

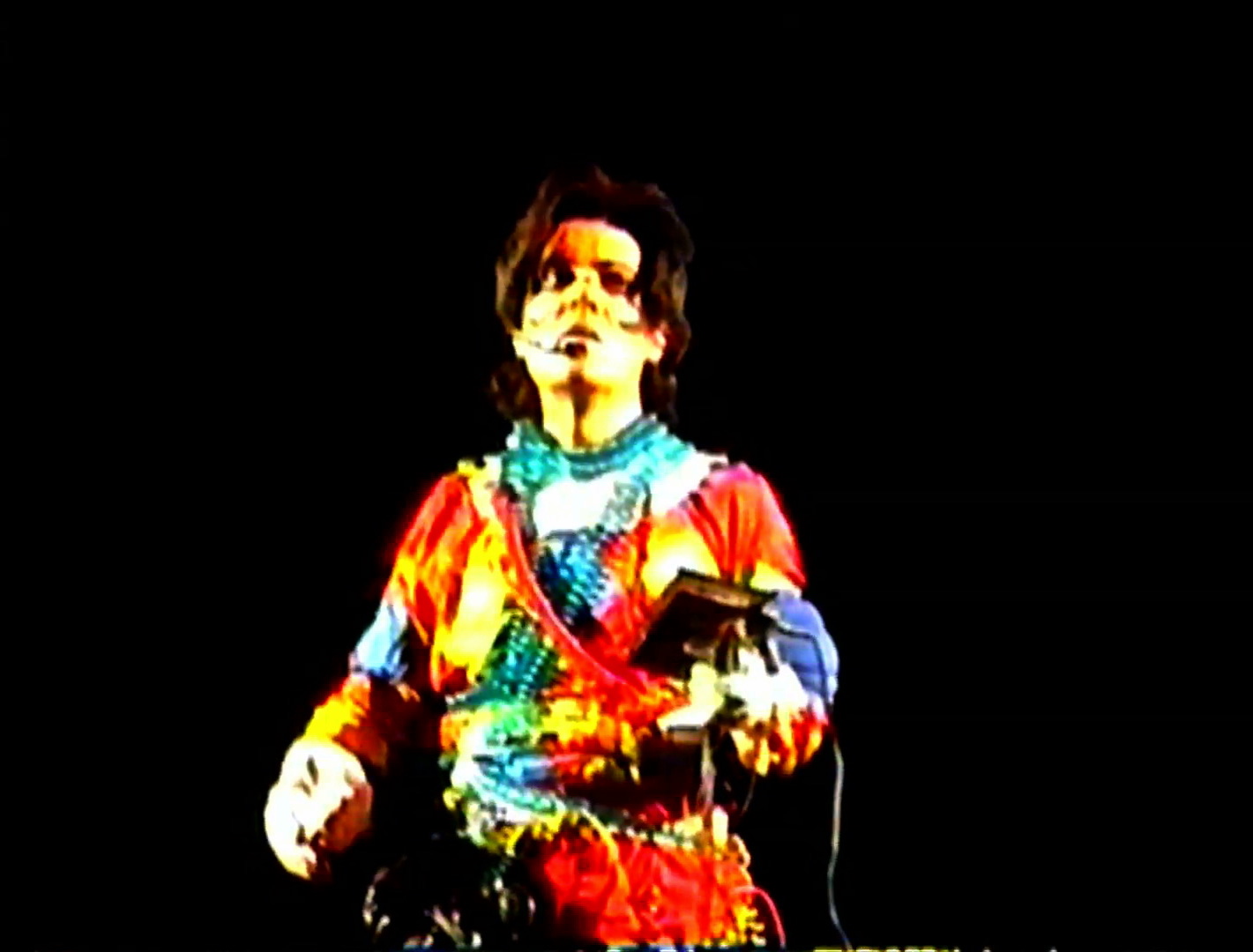

There is also a 1998 recording of his Cyberclown, which he refers to as a “mini opera”. Dressed as a Harlequin and enveloped by coloured telephone cables, he plays his doppelgänger Starlovsky. He performs a monologue, alone on stage: «A clown, a puppet, a marionette. Maybe I’m just a machine. More than human: immortal, eternal. Who am I?! […] In the sadism of power, of ignorance; in the sadomasochist violence of those who control my strings, my cables...»

On another tape is a concert at the Leoncavallo, a famous community centre in Milan. The year is 1999, and he performs in a punk rock style. The public is electrified. It is a young audience, different from his earlier fans. They cheer him while he lies on the stage, his face painted white, and he asks them, «What will become of the puppets that rebel, that rip their strings off? What happens to them? Will they perhaps learn to think?»

Another tape: Alberto Camerini holds an acoustic guitar; he is about to sing an eighteenth-century Venetian aria. While trying to disentangle from his stage costume, he addresses the audience: «I should get out of these fucking cables, but it will take hours. These are the strings of power: once you’re in, you can’t get out. […] Okay, I’m a clown, so when I talk about politics, I am... Not a fool, eh? I’m masked. So, do you want to hear this fucking Venetian aria, or you just don’t give a damn? Sorry. My usual buffoonery.»

I visit Alberto again a few weeks later. I bring him several reproductions of the Scherzi by Giambattista Tiepolo, one of the most mysterious series of etchings in the history of art. While he leafs through them, I ask him what happened after his taking part to the 1984 Sanremo Festival[4]. «Forty TV appearances, people delirious for you, getting in the car while everybody’s jumping on you, the barriers, the police... When you reach that, after a while you get used to it. And that’s the problem, because when the barriers and the police are no longer there, you ask yourself, “Hey, where are the fans?” And you realize that the magical moment is over. In three years I went from singing in basements to the Sanremo Festival; ten thousand people would come to my concerts; I felt like a rock 'n' roll superstar. But I just didn’t have the mindset. And, alas, I left the firmament of successful pop singers. I’m an expert at switching from reality to fantasy. […] Yes, it was hard. The record company dropped me. I toured all over Italy, trying to make the most of my fame. But it worked less and less, less and less... So, guys, that’s how it went.»

He puts down Tiepolo’s etchings, then adds, «Now I am studying the countryside circus of Harlequin in the 19th century: it’s when Harlequin abandons theatres».

During my last visit I give him another book about the Venetian painter: Rosa Tiepolo[5], by Roberto Calasso (2006). I ask him to read aloud a passage I have underlined:

Just as he had arrived without meeting any resistance, so he departed without arousing any regret, losing himself among the names of those of whom there is a confused, shadowy memory. No one suspected that with him vanished the last point of equilibrium in the visible. Elusive, precarious, and bewitching. Yet such was the case. Thereafter, even the possibility that that point existed was forgotten.

[1] Guy Debord, Commentaires sur la société du spectacle, Éditions Gérard

Lebovici, 1988.

[2] English translation by Kevin Attel: Pulcinella: Or Entertainment for Children, Seagull Books, 2018.

[3] Giorgio Agamben, in “Dal disastro ci salverà la viltà di Pulcinella”, interview by Alessandro Leogrande, in pagina99, n. 1, november 2015, pp. 24-25.

[4] The “Festival della canzone italiana di Sanremo” is the most popular Italian song contest and awards, held annually in the town of Sanremo, in Italy, and consisting of a competition amongst previously unreleased songs.

[5] English translation by Alastair McEwen: Tiepolo Pink, Bodley Head, 2010.