– Milano 2

Riccardo Giacconi

The city of number ones.

Pictures from Milano 2

2017

An essay on the neighbourhood of Milano 2,

in conjunction with the film Due.

Italian version published on Le Parole e Le Cose.

French version published on Revue Décor.

English Version

Every form of life structures itself in a ‘language’ that remains completely foreign and incomprehensible to us. [...] Every form belonging to the realm of the visible is, among other things, also a particular way of presenting itself.

– Adolf Portmann, Aufbruch der Lebensforschung, 1965.

Our escape from the city is the escape of those who seek the city elsewhere, who seek the contact of man with man in real, not cynical ways. It is a journey driven by the need to survive. It is a biological journey. Is our escape utopian?[1]

– Enzo Siciliano, Milano 2: una città per vivere, 1976.

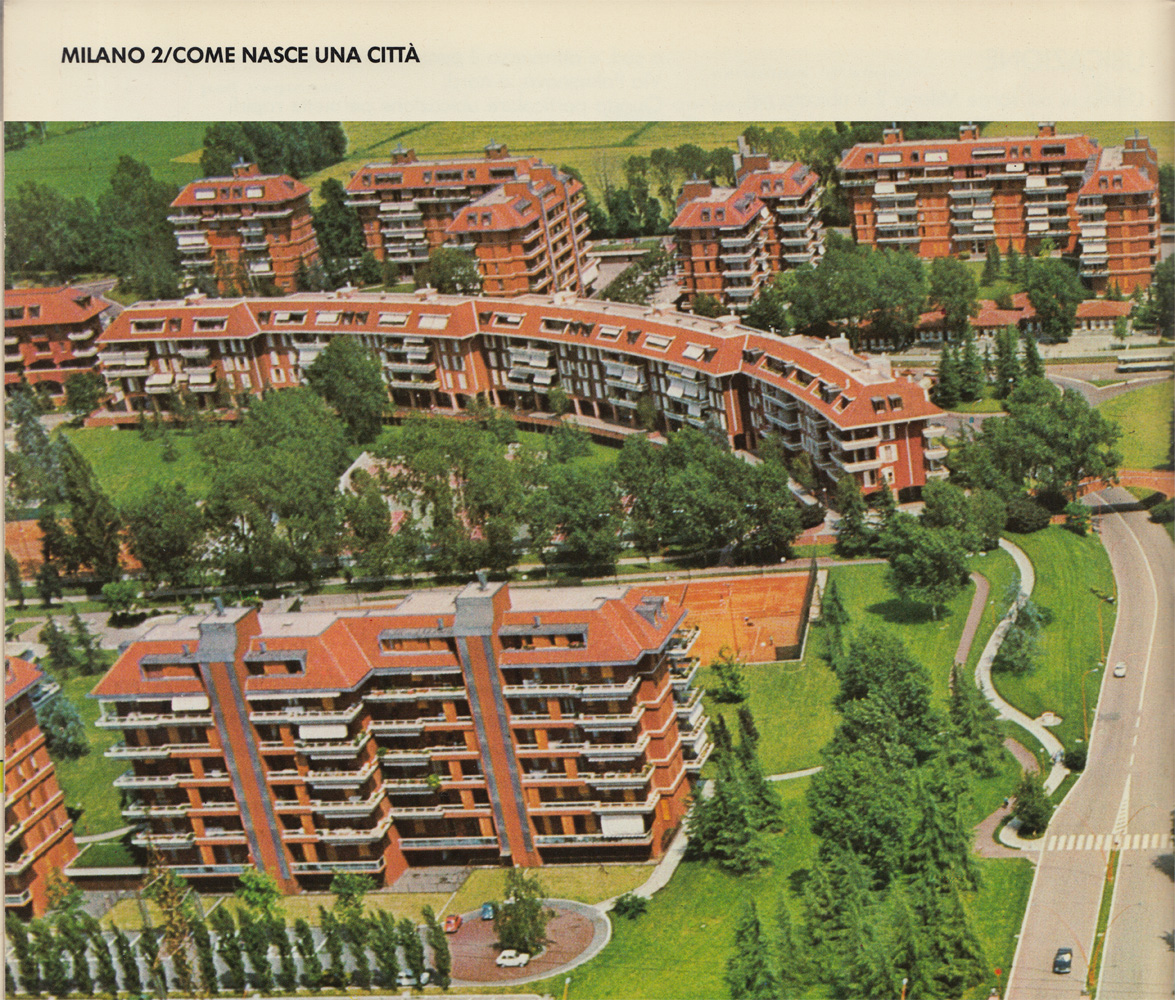

“I had recently graduated”, says Enrico Hoffer, one of the architects who designed Milano 2, the residential neighbourhood built by Silvio Berlusconi in Segrate, on the outskirts of Milano. “Together with three fellow university students we decided to set up a firm. We met Berlusconi through mutual friends, and that was our stroke of luck. He was planning to build a whole neighbourhood, and he asked us to come up with a project. We did, he liked it and he bought the land, which used to be a farm. We went on with urban planning and various constructing projects, which developed between 1969 and 1979. We shared a common understanding based on youthful enthusiasm, and we managed to put together something acceptable.” Hoffer smiles as he says the last sentence.

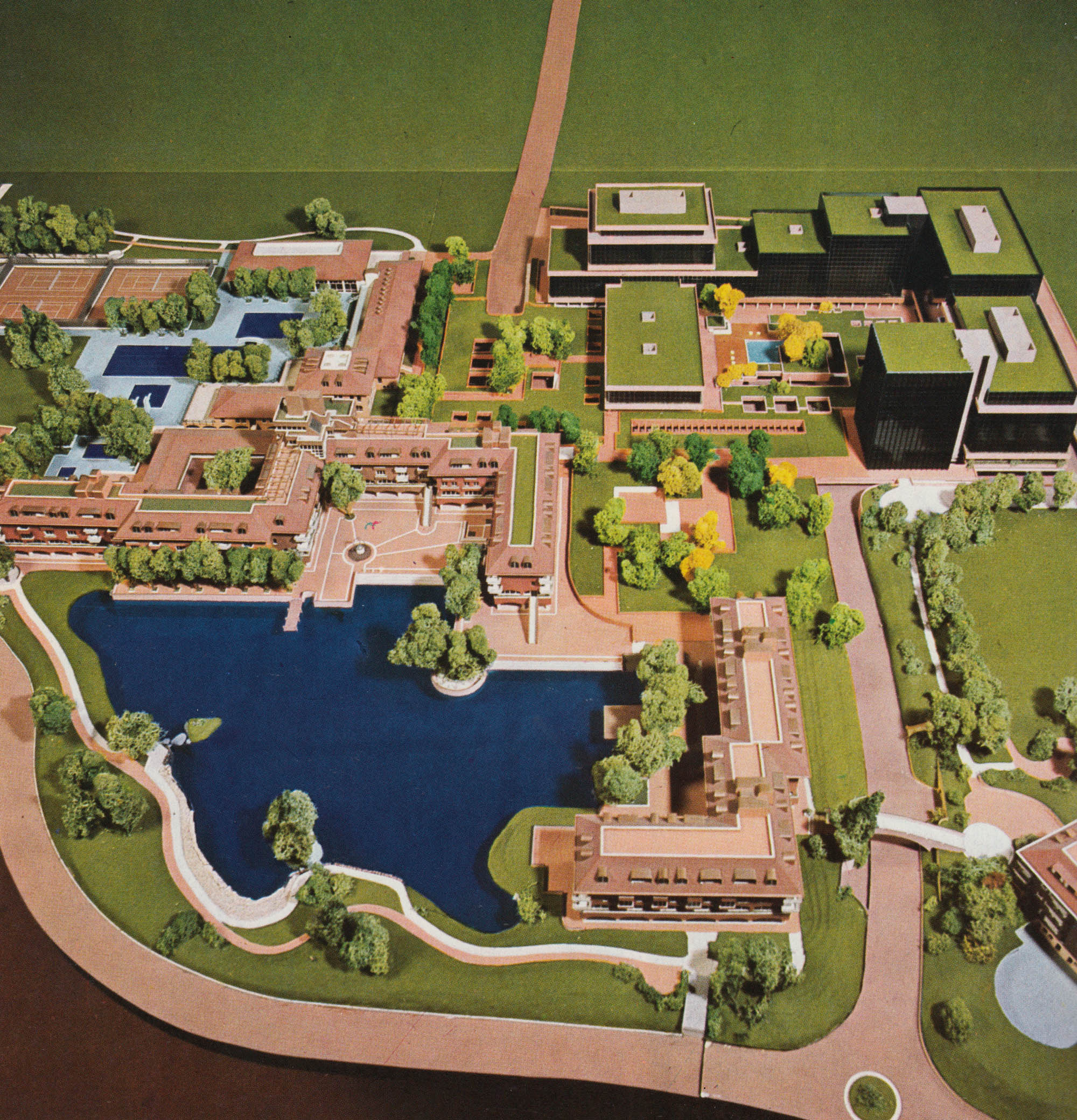

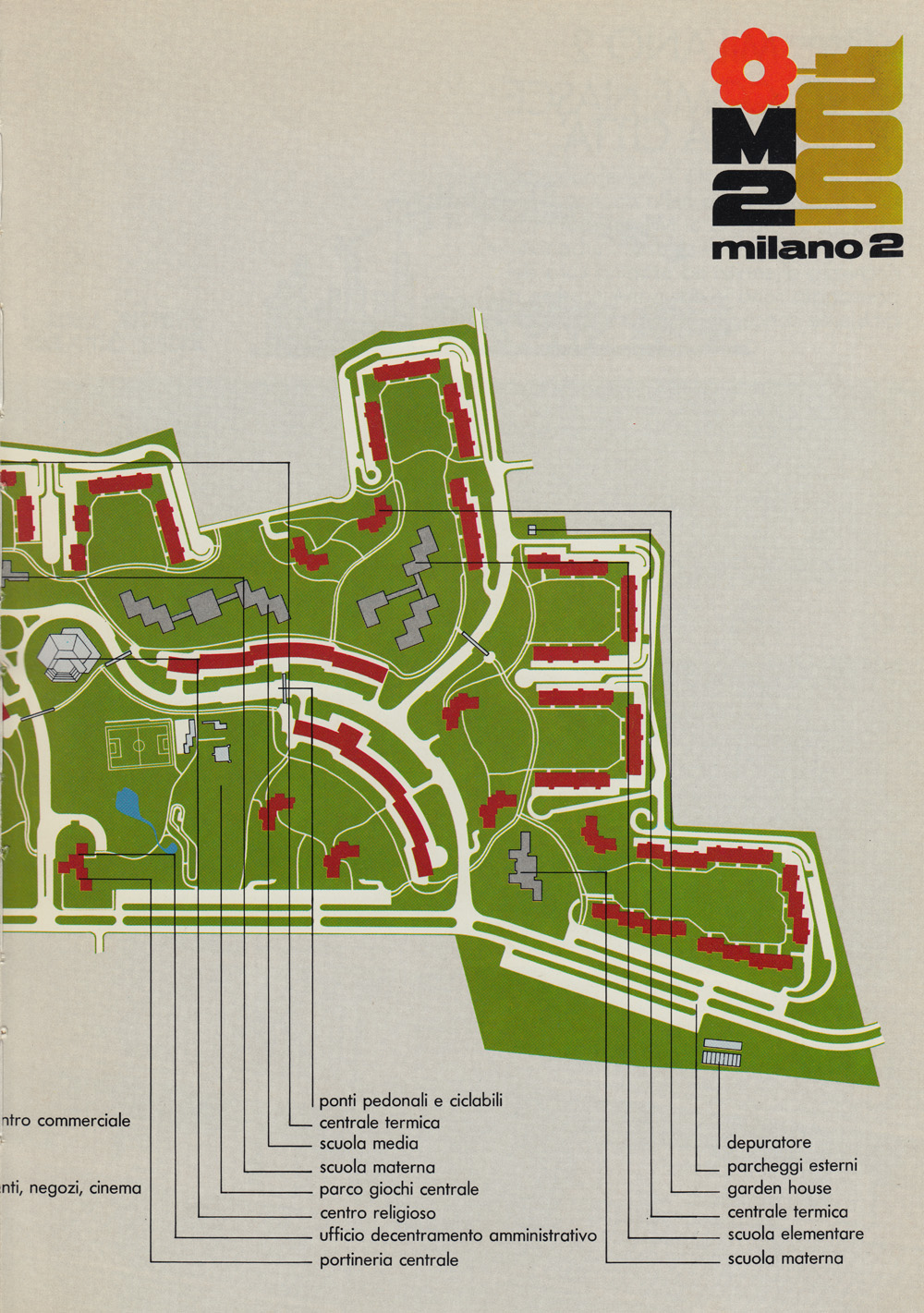

I spend a lot of time in Milano 2, in order to work on a documentary film about the neighbourhood and its evolution over time. At the Biblioteca Braidense in Milan I come upon a 1976 advertising brochure published by Edilnord Centri Residenziali, Berlusconi’s real estate company. It is called Milano 2: una città per vivere (“Milano 2: a city to live in”), and I am told that all of the first inhabitants of the neighbourhood (the so-called “pioneers”) had a copy of it waiting on their bookshelves when they entered their new apartments.

“Usually they were around forty and had a couple of children. They really felt like pioneers,” says architect Hoffer, “because when they arrived, they found a completely new reality, where even essential services were not in place yet. But there was a good simultaneous growth of housing and infrastructure: little by little came schools, shops, transports, a church, a post office, a bank, a Sporting Club...”

The image of a new world to be colonized by pioneers recurs also in the advertising brochure, for instance in a text written by journalist Gianni Brera:

In Milano 2, the miracle certainly appears to have taken place. The big city remains behind us. In ancient times we would have used the word ‘colony’. The people in excess find another distant place; a ruthless draw designates those who have to leave. Here, fortunately, the colony has arisen from a spontaneous choice. The new community enucleates itself without drama. Privilege is an industrious achievement, a good to be enjoyed together, in the most rational way possible.[2]

Brera describes the “privilege” holding the new community together in utopian, almost messianic tones: Milano 2 presents itself to potential buyers as a world to come. Indeed, the neighbourhood did not expand organically from an existing urban or social fabric; it was born as a pure idea, built from scratch on an empty lot.

Speaking of the early times, architect Hoffer remembers that “every Saturday morning a full page would be published on the Corriere [Il Corriere della Sera, one of the main Italian newspapers], with texts and photos showing the wonders of Milano 2. And floods of people came, ready to buy. Berlusconi liked to show people around: «look here, look there... ». He enjoyed it, that’s the way he is; he has always been a good salesman.”

The full pages on the Corriere della Sera had slogans such as “Milano 2: clean air operation”, or “Milano 2: it’s time to invest”, or the most famous: “Milano 2: the city of number ones”.

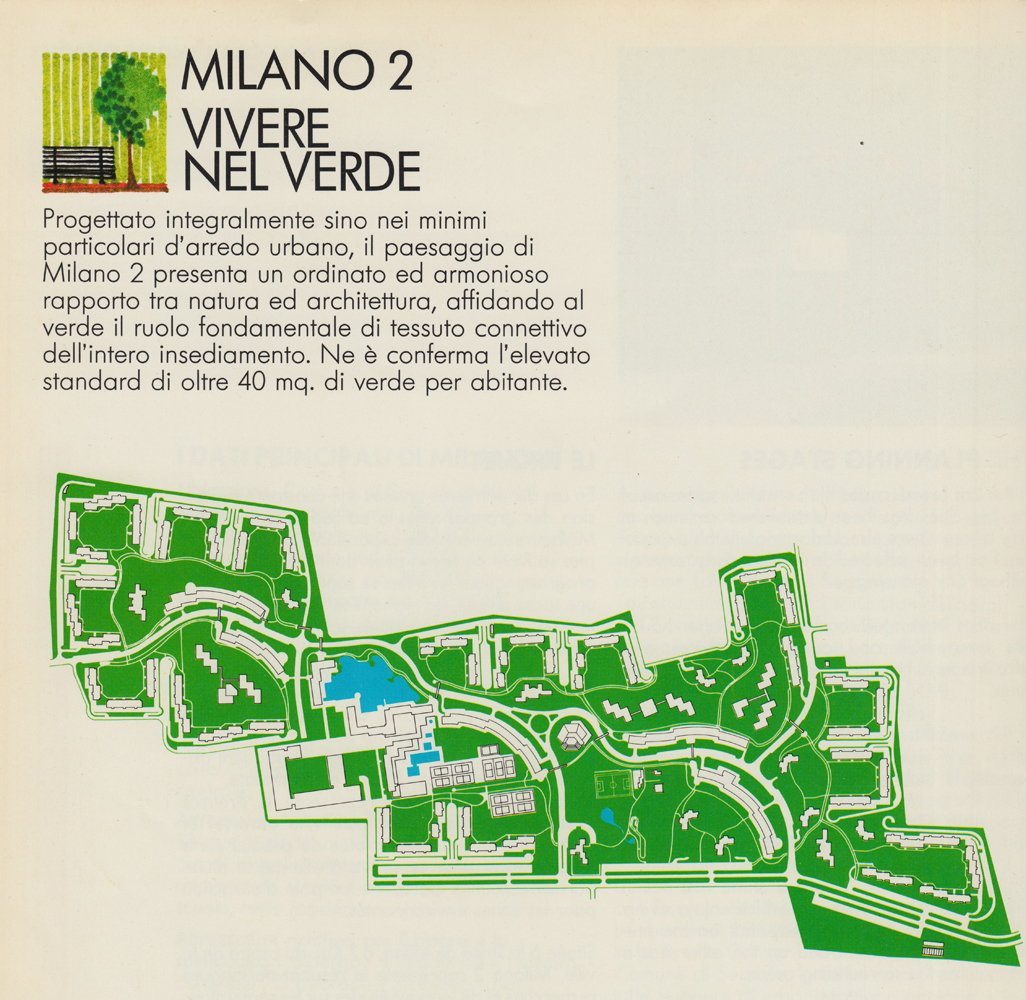

“The whole idea of a neighbourhood with lots of green spaces, where cars are almost never visible, was Berlusconi’s”, continues Hoffer, who designed the landscape of Milano 2. “He spasmodically followed what was being done in the technical department, getting into details. For example, he was very involved in the choice of trees. Together we would often visit nurseries looking for trees, in order to plant them in Milano 2. It was the first time that he really expressed himself as an entrepreneur – an entrepreneur with architectural ambitions. The general philosophy of the neighbourhood is his. Then, architects did the rest”.

The landscape was, from the beginning, one of the key points in the advertising campaign of Milano 2. The new neighbourhood was presented as an oasis of harmony between nature and architecture, in stark contrast to the pollution and the asphalt of downtown Milan. Such comparison is the focus of Natalia Aspesi’s text for the advertising brochure:

The physical landscape of Milan has become cruel, and it is bitter to endure it at times. So it is in the skin, in the ears, in the stomach, in the blood, where one feels the desire to experience Milan and at the same time to exorcise Milan: in short, to feel armoured emotions in a tough and tireless city and, at the same time, to feel vulnerable emotions in a sweet and quiet city. A Milano 1 to be at the centre of everything; a Milano 2 to find yourself.

[...] More than colours, proportions, greenery, soft hilly areas, neat street signs, peremptory separations between pedestrian and car traffic, the landscape in Milano 2 is composed of children playing, boys cycling, men and women walking, people moving in an unusual space, unconceivable in the other Milan.[3]

The advertising campaign evoked the image of an Arcadian, serene world; yet such world was perfectly parallel to the real city, which remained “just a stone’s throw away”. It was not just a real estate project, as architect Hoffer confirms: “All kinds of commercial motivations contributed to the success of the initiative: living in green spaces, creating a holiday atmosphere in the neighbourhood... It was something completely different than what was happening back then in smog-filled downtown Milan. It was a true form of life”. Upon hearing this, I am immediately reminded of a sentence pronounced by Michel Foucault in his last course at the Collège de France: “Revolution in the modern European world [...] was not just a political project; it was also a form of life.”[4]

Both reading the advertising brochure and speaking with the current residents of the neighbourhood, it becomes clear that “commercial motivations” (such as the escape from smog) acted hand-in-hand with another, concealed motivation. “The idea was to appeal to a class of wealthy people who wanted to leave downtown Milan, which at that time was unsafe”, a resident tells me. “Political demonstrations were taking place all the time, and we lived under the threat of terrorist attacks. That is why many of us left.”

The “form of life” advocated in Milano 2, where children can “grow up peacefully in green spaces”, locates itself entirely outside the political arena, far from the discussions, movements, risks and riots of the city. What the “pioneers” were buying, was a separation, both geographically/environmentally and economically (a “privilege to be enjoyed together”).

“Milano 2 has been terribly boycotted from a political standpoint, since the beginning”, Hoffer tells me. “At some point, even the judiciary intervened, because some charges were pressed against us. We had to fight, since the intelligentsia did not digest the project well. They began to call it «the ghetto of the rich» and things like that. Yes, those who purchased in Milano 2 were probably not from the working class, but we had a fairly large assortment of customers.” I ask him about the relationship between Milano 2 and the so-called riflusso (a term used to indicate a general resignation to the private sphere and a concomitant political and social disengagement, which characterized the transition from the 70s to the 80s in Italy). “The project was received as a political statement”, he replies. “The idea that a neighbourhood could be separated from the city and have an independent life was not well regarded, especially in the Seventies. Ideology, which also permeates urban planning, rejected this model altogether. Today, I think that similar projects are out of the question, at least in Italy.”

The launch of an experiment called “TeleMilano” turned the neighbourhood into a real laboratory, ushering a phase of radical transformation in Italian society. The 1976 advertising brochure devotes one of the last paragraphs to TeleMilano, introducing it as “the first cable TV with regular broadcast programs [...] The production studios are based in Milano 2 and are equipped with stationary and moving cameras, recording stations, a complete mixing system, videocinema [...] Since its first months of life, TeleMilano has witnessed an active involvement of the residents in the programs’ production.”[5]

“At some point”, the architect tells me, “he moved away from real estate and focused on his new idea: television. Everyone had discouraged him, but he went ahead and managed to put together TeleMilano, which at the beginning was conceived as nothing more than a service for the neighbourhood, with newsreels and reports on Milano 2 transmitted through the local network. Then the project evolved, expanded nationwide. Compared to Berlusconi’s ambitious idea of television, TeleMilano was just a first, small spark”. I ask him what was the role of architects in the television project. “We designed some studios, but television was no longer our job. Satisfied with Milano 2, he envisaged another endeavour, no longer in real estate but in media.”

I meet Debora Visconti, born and raised in Milano 2. In her book celebrating I quarant'anni di Milano 2 (“Milano 2’s fortieth anniversary”) she describes the beginning of the TV endeavour:

TeleMilano was the cable television of Milano 2. […] Entirely dedicated to the residents of the neighbourhood, the station was the result of an idea by Giacomo Properzj, secretary of the Republican Party of Milan. His fellow adventurer in the enterprise was Alceo Moretti, owner of the “Alfa” PR agency. Silvio Berlusconi rented Properzj and Moretti an apartment in the Residenza Portici: it became TeleMilano’s headquarters. Soon the two cable TV pioneers realized how costly the initiative was. So they handed over the business to Berlusconi, who soon transformed TeleMilano into a broadcast television, thanks to Law 103, which allowed local TV channels to transmit over the air.[6]

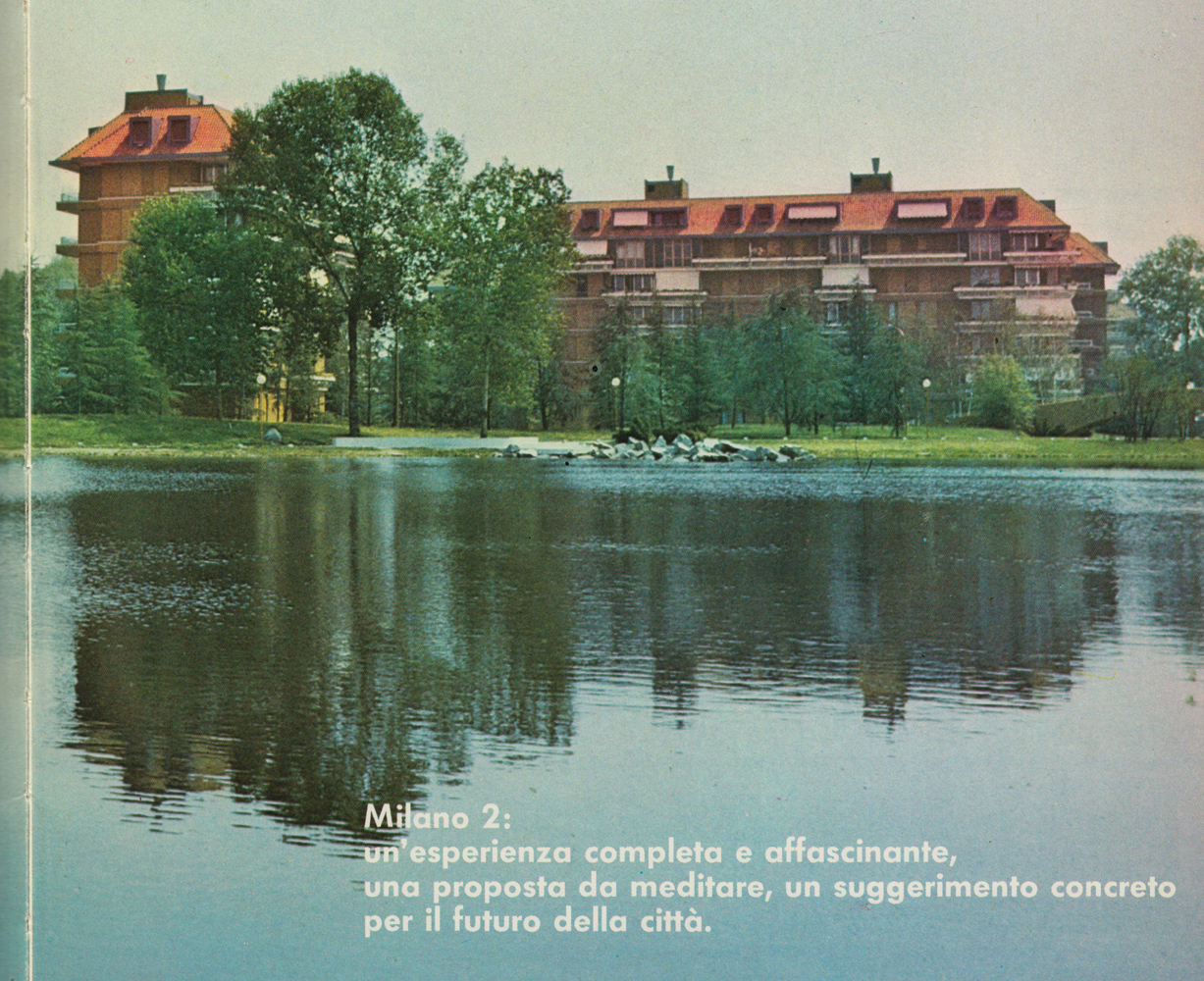

The station began transmitting in 1974 from the famous Palazzo dei Cigni (“Swans Building”), located in the main square of Milano 2, in front of the pond. TeleMilano would then become Canale 5, the first Italian private TV station and the bridgehead for Berlusconi’s media empire. The neighbourhood acted as a laboratory for the experiment: through the television medium, the “form of life” could radiate on a national level.

I show a first cut of my documentary to French writer Yannick Haenel, author of Je cherche l’Italie (Gallimard, 2015), a journal of his stay in Italy. According to Haenel, “the structural connection between Milano 2 and television reveals how the real estate project and the Berlusconist media culture share the same founding concepts”. What was hastily labelled as ‘pure entertainment’ in the early years of Italian private TV, was actually the announcement of a new “form of life”, which had left political engagement behind and abandoned any struggles to change the world. TeleMilano announced that the world to come had already taken place: it was Milano 2 – it was the prototype to transform the whole of Italy. The project had a political character from the beginning, long before the actual “discesa in campo”[7] in 1994.

In this perspective, the slogan that opens the advertising brochure takes on a broader meaning: “Milano 2: a concrete and fascinating experience, a proposal worth meditating, a concrete suggestion for the future of the city”. A few pages later, journalist Marco Mascardi reiterates it in other words:

Milano 2 is something more than a neighbourhood. [...] It is a new way of living life. If the model works, [...] then the commitment becomes enormous, because such model needs to be followed. Similar settlements will have to be built elsewhere. And so Milano 2 becomes a prototype, a matrix.[8]

The real estate project included in embryo both the political and the media projects: they were integral to each other. Together, they tended towards a “new way of living life”, towards the “new community” that “enucleates itself without drama” foreseen by Gianni Brera. Everything was already there, intertwined around the Palazzo dei Cigni: architecture, communication, government. The three aspects jointly inhabited the neighbourhood and, as Carlo Mazza Galanti writes in an essay on his childhood in Milano 2, even their personifications could be found strolling around: comedian Jerry Calà, “who lived in the Spiga Residence”; AC Milan footballer Ruud Gullit, who “often played basketball on the court in front of the church”; actor Raimondo Vianello at the barber’s. Or Marcello Dell’Utri, Forza Italia co-founder and convicted mafia criminal, “sunbathing by the residents’ swimming pool”.[9]

Or architect Hoffer, who lives in Milano 2 since the Seventies, when he was overseeing its construction. I ask him how he sees the future of the neighbourhood. “It will go on”, he replies, “hoping that it will be preserved in the best possible way. Many changes have been made over time; others will follow. At the beginning there were three kindergartens, two elementary schools and a middle school. Now the birth rate has changed: some structures have become superfluous”.

In October 2016, the last images were transmitted from the television studios in Milano 2, which had begun broadcasting via cable in 1974, and had hosted classic Italian TV shows, such as Striscia la Notizia and Paperissima, as well as newsreels like Studio Aperto and Tg4.

Wandering around the neighbourhood today, I try to distinguish the signs time has left in this place, conceived as the laboratory for an Italy to come. I walk around the pond. I pass by the Palazzo dei Cigni, that bears today the logo of Mediaset, Berlusconi’s media company. I have lunch at the company cafeteria. A couple of times I bring non-Italian friends with me. It is hard for them to sense how such a profound change in Italian culture began right here, in these suburbs. This residential area does not lend itself well to being imagined as scenery for power clashes, as the outpost of a media empire, as the case study for a large-scale social experiment. Yet, it all started right here.

I often perceive a melancholic undertone in my conversations with current residents. Just like a house after a party, it seems that Milano 2 and its “pioneers” have been left behind. After decades of Berlusconism, today the neighbourhood does not look like anything special anymore; the “form of life” of which it was a prototype has already been spread everywhere.

I get lost. I ask an elderly lady for directions, we start chatting. “I cannot stand living here anymore”, she tells me. “It’s not as it used to be – we are all old now. I bought an apartment here in the Seventies. Then, my kids went to study in Milan and ended up staying there. I wish I could go back to Milan too. I try to go there as often as I can.”

Yet Milano 2, as many say, has aged well. Everything seems in good condition: playgrounds, hedges, ponds, reception desks. There is no dirt around. Some storefronts may be empty, but the neighbourhood did not turn into a ruin. Perhaps, into a monument. Like the one in the middle of the main square, sculpted by Pietro Cascella and donated to the residents by Berlusconi. Like those monuments built to celebrate an idea – those that end up staying there, always the same, while everything around them changes.

[1] Milano 2: una città per vivere, Edilnord Centri Residenziali, Milano 1976, p. 19.

[2] Gianni Brera, in Milano 2: una città per vivere, p. 34-35.

[3] Natalia Aspesi, in Milano 2: una città per vivere, pp. 32-33.

[4] Michel Foucault, Le Courage de la vérité. Le gouvernement de soi et des autres II. Cours au Collège de France, 1984, Seuil, Paris 2009. Lecture of 29 February 1984.

[5] Milano 2: una città per vivere, p. 178.

[6] Debora Visconti, I quarant'anni di Milano 2, 2011.

[7] On 26 January 1994, Berlusconi announced his decision to enter politics, (“enter the field”, in his own words) presenting his own political party, Forza Italia.

[8] Marco Mascardi, in Milano 2: una città per vivere, p. 15.

[9] Carlo Mazza Galanti, Mi ricordo Milano 2, in “All’ombra del Palazzo dei Cigni”, published on “The Towner” on 16 May 2016. http://www.thetowner.com/it/milano-2-palazzo-dei-cigni/ See also Filippo De Pieri and Paolo Scrivano, Milano 2, abitare nel marchio, in “Il Manifesto”, 14 July 2001, p. 12.